Below is a small selection of Bad Bolt Beta from the Access Fund and the American Safe Climbing Association.

We encourage you to check out the full Access Fund article and the ASCA Resources empower yourself with the knowledge to identify and report bad bolts to the SLVCA.

We encourage you to check out the full Access Fund article and the ASCA Resources empower yourself with the knowledge to identify and report bad bolts to the SLVCA.

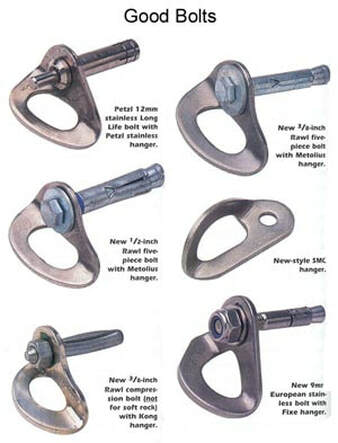

Good or Bad Bolts?

Two photos below courtesy of the American Safe Climbing Association

Clipping bolts should never be a mindless endeavor. The bolts and other fixed anchors that keep us safe while climbing require thoughtful use and maintenance to remain in sound working condition. Eventually even the best hardware will need to be replaced and if abused the life span can be significantly shortened. As climbers we have a responsibility to understand the systems we use and what constitutes a bomber vs. sketchy piece of pro.

Button heads & Star Dryvins

|

Climbers should be wary of all button heads, a type of compression bolt that is typically only 0.25 inches thick and 1.25 inches long. Button heads have a split shaft, which means less than half of the 1.25 inches of length is actually pressing against the bolt hole to keep it in the rock. There are numerous incidences when these types of bolts have been removed with little more than a few hard jerks using a quickdraw. These bolts can vary in pullout strength in granite, but consider them downright dangerous in softer rock, such as sandstone or limestone.

|

|

Another suspect bolt type is Star Dryvins, typically called star drives, can be identified by the star stamped on their heads. Star drives tend to have a greater degree of variability in terms of how bomber they are. Sometimes they come ripping out of the wall with a quickdraw yank, but at other times, they can prove quite difficult to remove.

|

Good Bolts, Bad Placement

|

While button heads and Star Dryvins are red flags by themselves, other bolts may still be dangerous. Even bolts that were specifically designed for rock climbing—rather than construction uses like button heads and star dryvins—rust and corrode with age. Keep an eye out for any visible rust. On a typical wedge bolt, the outer threads and nut may be blackened with rust. For sleeve bolts, you can unscrew the hex head and pull the bolt out to examine the degree of corrosion occurring inside the sleeve.

|

Sketchy Hangers

|

Homemade hangers should also be treated with great suspicion. These homemade pieces ranged from hacked-off bedframes to full-on weld jobs. Some areas, such as the Red River Gorge in Kentucky, originally had loads of these homemade hangers. In the Red, Porter Jarrard was nearly as famous for his hangers as he was for his iconic sport routes. Because these types of hangers are homemade and vary greatly, their ultimate strength cannot truly be known, making their safety questionable. For one, they are not stainless steel and have been in the rock a really long time, so the forces of corrosion have been at work for decades.

|

Coldshuts

|

There are two types of cold shuts, open and closed, and both are dangerous. Many cold shuts were welded in a climber’s garage. Explaining the danger of that, Sandor Nagay wrote in Climbing magazine, “None of us would climb on a rope that our buddy wove in his garage, but many of us trust cold shuts implicitly.”

Nagay, a mechanical engineer, and Will Manion, a civil engineer, did extensive testing with cold shuts, including both 3/8-inch and1/2-inch versions. The variances in strength were extreme, ranging from 2,120 pounds to 8,180 pounds, with almost all of them failing at the weld. By comparison, most modern bolt hangers have an average strength of at least 6,400 pounds, about twice the force a 175-pound climber can generate during a lead fall. Nagay and Manion also found that cold shut strength was not consistent even among batches of new, unused cold shuts from the store. It should be noted that study was done in 1997, when most cold shuts were fairly new. Because of the variability, much like homemeade hangers, they should be replaced. Regardless of type or brand, worn hangers also are a concern. The inner edge of virtually any modern hanger—where the carabiner rests—is relatively sharp and not meant for rappelling off of directly. When this inner edge gets nicks or burrs on it, it can transfer that damage to your carabiner and, ultimately, your rope. Damage to the hanger’s edge can be caused by a variety of things, including whippers, hang-doggging and rock fall. But fortunately, it’s easy to see. Hangers with smooth edges—such as cold shuts and Metolius Rap (aka Fat) Hangers—also become worn, but the damage is different. The worst offender among the smooth hangers are open cold shuts, which are just what they sounds like: The metal does not form a solid, or “closed,” loop sealed with a welded joint. This allows climbers to simply drape the rope over them and lower down, and they’re used almost exclusively for single-pitch anchors. The problem is two-fold. First, the hanger is simply not that strong and is prone to bending and “opening” even more. Also, because they are designed for looping the rope directly over them, climbers tend to lower and toprope directly through them, causing wear more quickly. |

You might see some coldshuts at the anchors of climbs in the San Luis Valley - if you see any, please report them to the SLVCA so we can update them with bomber anchors!

|

Great job on making it this far. However, this is merely a brief overview. Go to Access Fund to read more and educate yourself!